My life as a Jupyter pioneer

I’ve worked with :Jupyter notebooks for many years. Almost—but not quite!—since their inception.

I was lucky enough to be a professor at Berkeley in 2014 when the technology was emerging in education. People associated closely with the Berkeley data science program pretty much invented this stuff. I developed a ‘connector’ class in geography as a contribution to the nascent Data Science major. The (I believe correct) thinking was that that it shouldn’t be possible to graduate in Data Science alone, and that all students should have some kind of domain expertise in the form of another major in a traditional discipline. To encourage this line of thought students taking ‘data science 101’ (in fact :Data 8 The foundations of data science) are required to take a parallel half-credit ‘connector’ class in some other discipline.

I developed Geog 88 Data science applications in geography which was was my first experience with notebooks. It was also my first encounter with a very limited (at the time) geopandas. So limited that I had to hack together some code to make waiting for it to plot polygon layers bearable. As I recall the problem was that geopandas was iterating over the polygons in a dataset using a for loop and plotting them one at a time. The fix was to convert a GeoDataFrame to a PatchCollection and plot that instead. Anyway, they’ve fixed that problem now so this is ancient history. That was my first close-up and personal encounter with matplotlib a python module I continue to hate and love in near-equal measure to this day.1

And so to Aotearoa

Anyway, in an ideal world, I’d say ‘and the rest is history’ at this point, but… while the trajectory of Jupyter notebooks has been onwards and upwards from there, my personal journey with them has been rather different.

We came back to Aotearoa New Zealand in 2018 for uh… reasons (not unrelated to more recent events in the US) to a position as Professor of Geography and Geospatial Science at Victoria University of Wellington. Taking the second part of that moniker (geospatial science) somewhat seriously, I was excited to advocate for using python notebooks in teaching, and… well… basically I hit a brick wall. Turns out that Berkeley was probably definitely five (maybe even more) years ahead of New Zealand universities in uptake and support for Jupyter notebooks and the associated cloud computing needed to make effective use of the technology in the classroom.

It’s too hard

At first when I asked for IT support to set up notebooks in the lab I encountered blank looks. Then after some research, mostly more blank looks, followed by some version of “it’s too hard” in the context of general computing labs where the GIS classes are taught. We briefly explored the free tier of Azure notebooks then on offer to the university through its everything-MS-all-the-time Microsoft subscription but the CPU cores provided through that deal were underpowered. I also contemplated using the Jupyter capability then emerging in the Esri suite, but that was ArcPy, which was and remains a clunky and unwelcoming introduction to the elegant python programming language. A most ‘unpythonic’ place to begin.2 The more friendly ArcGIS API for Python had yet to emerge (ArcGIS Pro had barely emerged at this point.)

So… I shelved things for a while, but returned to notebooks when it came to developing a class in Geographical Computing as part of the eventually-doomed postgraduate program in GIS at VUW. Given lab support limitations, I wound up teaching students about conda environments so we could all setup the same python environment on our computers and took it from there. So we never used Jupyter notebooks in the client-(remote) server mode, but instead in client-(local) server mode. It was fine, if a little deflating, given that Berkeley had been delivering notebook based instructions to classes of several hundred or more students five years earlier! On the upside, students did get to learn about virtual environments and all that good stuff.

Anyway… fast forward to today

I still use notebooks all the time. It’s probably not a great habit, but they’re my go to for quickly exploring coding ideas. I even use them as a high level ‘test harness’ of sorts for the weavingspace module.

And now, I’ve been asked to develop python training materials for a client. In that context, I once again have run into organisational IT. In brief, the course is to be delivered via Jupyter notebooks, but IT want the supplier (that would be me) to provide a solution completely outside their infrastructure. In other words, no in-house Jupyter hub or similar, student login credentials to be provided by me, and so on.

Which meant I was faced with the question that VUW IT were posed by me back in 2018: can you support Jupyter notebook based instruction?

At first I did the obvious thing and explored options at a number of more or less shrink-wrapped solutions such as Google Colab, CoCalc, and SaturnCloud. What I found there was more confusing than helpful. CoCalc is the only one actually focused on teaching/training and its pricing model is hard to unpick. The interface for setting up a course is also less than intuitive. The other two, like most offerings in this space are so focused on the work of machine-learning teams that it’s not at all obvious that they would work for my use-case: a relatively small group of learners working with a limited (and niche, i.e. geospatial) set of python modules. This pattern was repeated at all the options I looked at.

And so,3 I thought it was time to roll up my sleeves and give setting up my very own Jupyter hub a try. How hard could it be? Really really hard I thought. After all, fully grown university IT departments have shuddered at the very thought.

Reader, it’s really not that hard!

Seriously though, it really isn’t.

It’s so easy that I’m not going to provide tutorial advice, but instead link you to the excellent instructions I followed at The Littlest Jupyter Hub. It took about 45 minutes.

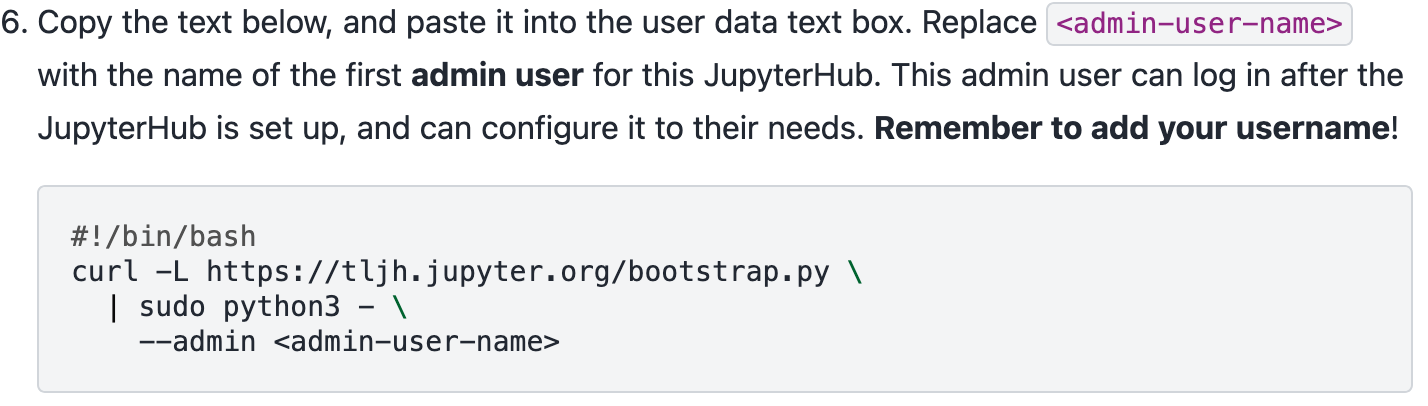

But that included registering payment details at Digital Ocean4 and two false starts, where first, I ignored a clear bolded instruction in the setup guide5

and then I forgot to give the server a more memorable name than the default one assigned by Digital Ocean (this isn’t a problem as such, just annoying).

What can I say? It had been a long day poring over complicated cloud computing pricing structures and negotiating 2FA on new services I had only joined to take a look. If you avoid those false starts and already have a cloud computing subscription, you could be up and running in under half an hour.

It took a further half hour or so to configure things on the server itself, setting up the default user environment, and most importantly setting up https rather than http access (for this you need an internet domain name on which you can establish subdomains).

But really… I have had more problems getting IMAP access to an email account via gmail to work properly.

The hardest parts

The biggest obstacles to doing this are most likely:

- For

httpsaccess you need an internet domain on which you can set up a subdomain. This is technically straightforward but you do need a domain you own and have some control over. - Cloud compute pricing plans are pretty much meaningless until you actually sign up. You won’t know what you need until you start using it, and you won’t know what that translates to in terms of actual compute you are paying for until you have some people logged in and using a server. It’s reminiscent of the worst days of mobile phone plans.

The latter is a real issue. I will have to on-charge the compute costs to the client and we won’t know what those are until after we’re done. We do have a no-cost (but some nuisance) plan B involving the somewhat amazing Github Codespaces, and we might even end up using that because of the cost, or more accurately, the uncertainty around the cost of the Jupyter hub solution.

But my main reflection on this experience would be to strongly encourage any organisational IT team to take a look at this. Chances are you are already using cloud compute infrastructure, so what’s the holdup?!

Footnotes

Actually, probably

hate > love. If there is a more convoluted API thanmatplotlibanywhere on the planet, I really don’t want to know about it.↩︎Yes… I’ve drunk the python koolaid.↩︎

Egged on, I should acknowledge, by an academic buddy↩︎

A choice dictated more than anything by them appearing first in the list on the tutorial page: do yourself a favour and give one of the options with free compute hours a try first.↩︎

RTFM!↩︎